The Barksdale Legacy

Jim Barksdale grew up in Mississippi, the third of six sons, competing for the "Boy of the Week" award with brothers Jack, Thomas, Claiborne, Bryan and Rhesa.

For each week's outstanding good deed, the title-holder earned a silver dollar dangled by their parents.

"Rhesa would polish Claiborne' baby shoes," Jim Barksdale recalled as an example, "but one day, the polish was kicked over. As Claiborne would say later, 'There was no Boy of the Week that week.'"

Over time, the shoe polish, the boyhoods and the supply of silver dollars dried up — but not the good deeds, least of all with Jim Barksdale.

The renowned business executive and philanthropist has contributed millions to initiatives for the betterment of his home state, including one whose 20th anniversary arrived this year: the Barksdale Scholarships at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

The winners don't receive a silver dollar, but thousands of dollars for an education instead. They do receive a title, one that will stick with them for longer than a week: M.D.

Today, dozens of scholars have benefited from these gifts, including a large number of African-Americans, many of whom are now practicing physicians in this state.

How and why this happened is fairly easy to explain: Jim Barksdale came across a "snake."

THE FULLNESS OF TIME:

Dr. Sonya Shipley grew up in Puckett, a southeastern Rankin County

town known for its 350 or so citizens, its eight-ounce Billy

Burger, and its proximity to the 95-mile long Strong River.

"Little girls who come from where I came from don't get to sit in the place where I get to sit every day," Shipley said.

An associate professor of family medicine at UMMC, Shipley made this point while sitting in an office decorated with a Howard Miller tabletop clock. Attached to the timepiece is a gold plaque inscribed with her name below the words "Bryan Barksdale, M.D. Scholar."

"That scholarship helped make this possible," she said.

Because of tall achievements and high scores, Shipley, formerly Sonya Clemmons, was accustomed to being paid to go to class, including at Millsaps College. So, when she learned she had a large, renewable scholarship to attend medical school, her reaction was: "OK. I got another one."

"I was incredibly grateful. But once I got into it, the longer I walked this path, the more appreciative I became."

By 2008, her appreciation ran as deep as the Strong River runs long. That's the year she graduated from the School of Medicine — "with zero debt," she said.

Originally, the scholarships provided a full ride; today they pay for most of a student's medical education, in spite of costs that have gone up since Shipley graduated. Estimates say today's medical student pays between approximately $32,000 and $37,000 each year in total direct costs at UMMC, not including housing/food, transportation and more.

"I don't know that words truly capture how eternally grateful I am for this generosity," Shipley said.

"The first dollar I earned was mine. I was free to live without a huge burden hanging over my head. I also felt like it gave me freedom of choice in my specialty. Because I never really had to look at how much money I would make, that made my choice easier."

Shipley's interest in medicine surfaced even before she participated in the Rural Medical & Science Scholars program at Mississippi State University in high school, which enabled her to take college algebra and zoology, and shadow a physician. "That solidified my decision," she said.

She was the first in her family to go to medical school. "Which I think is also part of why I was, on some level, a bit naive about exactly what I was receiving," she said.

"Now, I'm sitting here staring at a clock I was given my senior year in medical school. It's still marking the time."

NETSCAPE ARCHITECT:

In January, a six-part miniseries aired on the National Geographic Channel featuring the story of Netscape Communications Corp. during the exhilarating days of the web-browser innovator's infancy.

"Valley of the Boom" combines scripted drama with documentary-style interviews and imagined scenes capturing the breathless lunacy of the 1990's dot.com explosion and the birth of the internet, mid-wived in no small part by Netscape and its low-key, level-headed president/CEO at the time, Jim Barksdale.

Asked what he thought of actor Bradley Whitford's portrayal of Jim Barksdale, Jim Barksdale said: "I thought he should have been better-looking. I was hoping for Bradley Cooper."

Barksdale's deadpan delivery would make anyone think twice about taking him on in poker or Open Mic night at the Comedy Store.

"I thought he did a good job,"he added, more seriously.

In one scene, Whitford-as-Barksdale wields an affably lethal Southern charm, explaining to two of his executives that if they don't settle their dispute, he'll fire one of them — by flipping a coin. Problem solved.

Ancient history, or English lit, majors might call this cutting the Gordian knot. Barksdale might call it "killing a snake."

Living in Mississippi, you're liable to run across a snake or two. Barksdale spent his boyhood in Jackson, the son of a banker who was the son of a doctor.

"A great fellow, a loving fellow," Barksdale said of his father. "A big heart." His father, he said, was married to "the world's greatest mother."

John "Jack" Barksdale Jr. and Mary Barksdale brought up a raft of accomplished sons, including the four surviving brothers: a physician, Dr. Bryan Barksdale, UMMC professor of medicine and cardiologist; a federal judge, Rhesa Barksdale; an attorney, Claiborne Barksdale; and "No. 3," who served as CEO of two other industry creators before bringing his systems-application know-how to Netscape.

"We were normal kids," said Jim Barksdale, who wasn't joking. "We went to public schools here in Jackson. It was a happy life."

Throughout that life, his mom and dad made it rain silver, although Barksdale can't say how often he won one of those shiny dollars. "I'm sure Rhesa knows how many times he won."

There are winners still — those who benefit from the Barksdale predilection for compensating accomplishment, a tradition the brothers were absorbing when one of them was still in baby shoes.

QUEST OF HONOR:

Dr. Channing Twyner, a graduate of Murrah High School in Jackson,

became a President's Scholar Athlete of the Year at Nashville's

Belmont University, where he ran track and played soccer.

He was accepted into the Wake Forest Post-Baccalaureate Premedical Program and was a candidate for medical school there, until he received a notification containing five simple words: "The Fred McDonnell, M.D. Scholarship."

Bye-bye, Winston-Salem.

The award helped him out "tremendously," said Twyner, assistant professor of anesthesiology at UMMC. "Without it, I most likely would have had to take out student loans. It was a pretty easy decision to accept it. It was an honor."

It was an honor he might not have appreciated so much until his senior year in college, after he came home for the Christmas break. "My mother had set up a meeting with Dr. Claude Brunson," he said.

Brunson, who this year announced his retirement as senior advisor to the vice chancellor, external affairs, was the chair of the Department of Anesthesiology when he visited the not-quite-aspiring medical student.

"That meeting had a lot to do with why I chose anesthesiology," Twyner said. "Until then, I wasn't even thinking in particular about going into medicine. Sometimes mothers do know what's best."

After earning his medical degree, Twyner left his mom for a residency at the Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, following that with a fellowship at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine — which, like North Carolina, lost him to Mississippi.

Twyner might been "pulled" to stay in Alabama at one time, he said, but under the scholarship's terms, he had committed to returning to this state as a physician for at least five years.

"Without it, maybe somewhere on this journey, I could have ended up somewhere else," he said. "I'm happy to be here, being an anesthesiologist and doing pain medicine.

"I enjoyed learning and training here. I've enjoyed being home."

'LOVEYOUMEANIT':

Jim Barksdale graduated from the University of Mississippi in 1962

with a degree in marketing that he plugged in at IBM, selling

computers there before helping deliver a computerized

package-tracking system to his next employer, FedEx.

His next act was to dial it up at a cellular communications business whose prosperity prompted its purchase by AT&T Wireless. His work done there, Barksdale downloaded his talents to Netscape in 1995, staying on until AOL bought it in 1999 for $10.5 billion.

Barksdale — the "Valley of the Boom" version — ran Netscape with homespun aplomb, urging his troops to cut through the Silicon Valley chaos by focusing on "the main thing," which is, as he said, "to keep the main thing the main thing."

As others have testified, the main thing for Barksdale has been to make his home state a better place. To that end, post-Netscape, he created a windfall for UMMC in general and for the practice of medicine as a whole — the kind of thing he and his late wife of almost 40 years, Sally McDonnell Barksdale, had been at for a while.

In 1997, the couple had given Ole Miss $5.4 million to create what is now the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College — "to keep the best and brightest in the state," as Barksdale said at the time.

Three years later, the Barksdale Foundation granted $100 million to the state to stifle illiteracy, through the Barksdale Reading Institute, led at one time by Claiborne Barksdale. The donation also funded the Mississippi Principal Corps, a program to develop highly-effective, homegrown school administrators.

The year before that gift was announced, Barksdale had a momentous encounter with Dr. Wallace Conerly, UMMC's vice chancellor at the time.

"He came to me and explained that all the best and brightest black students were being recruited away from the medical school," Barksdale said. "They were being given full-ride scholarships. We were tired of losing them."

This was the snake he decided to go after — with a $2 million stick. With that endowment, he and Sally hoped to encourage talented African-Americans to stay in Mississippi for their medical education, also with generous scholarships.

"This state is about 37 percent African-American," Barksdale said, "and they're underrepresented in health care, especially as physicians. We need more."

The couple named the scholarships after physicians in their families: Dr. Bryan Barksdale, Dr. Don Mitchell and Dr. Fred McDonnell. More than 50 of these students have been awarded these annually renewable grants.

"For so long, we didn't have many black medical students, or black

students in other schools," said Dr. James Keeton, UMMC vice

chancellor emeritus of health affairs and dean emeritus of the

School of Medicine.

"When Jim Barksdale started giving us those scholarships, Tougaloo

College stopped being a direct pipeline to Brown University for

black medical students," said Keeton, Medical Center vice

chancellor for nearly six years, starting in July 2009.

"I happened to meet the dean of Brown at one time and he told me they weren't getting many people from Tougaloo anymore. I told him, 'I intend for you to get not a single one ever again.'"

Barksdale's personal and philanthropic partnership with his wife Sally ended in December 2003, upon her death from colon cancer. A couple of years later, a new alliance emerged after a book-signing, where he met the woman he calls "the star of Simpson County."

Donna Kennedy, a self-described "Sweet Potato Queen, Ret.," was at the time an active acolyte of THE Sweet Potato Queen, best-selling author and Mississippi's own contributor to world peace, Jill Conner Browne.

To explain the appeal of the Sweet Potato Queen would take a small library — which is about what Browne has produced on the subject; suffice it to say, Donna verified her royal lineage by signing one of those books to Jim Barksdale: "Loveyoumeanit."

That's the way SPQ's signed everything, which Barksdale didn't know then. "That one time, she meant it," he insists. "I stared at it all night."

A product of the south Mississippi town of Magee, Donna Barksdale, who once ran a clothing design business, has woven a voluminous career as a leader in education, business, philanthropy, civic endeavors and more. She presided over the Junior League of Jackson when it voted to support the Children's Cancer Clinic at UMMC.

"The Medical Center truly accepts everybody," she said. "That's why I love it so much. It's truly doing mission work."

Fealty to UMMC is something Donna and Jim already had in common before they met. "The Medical Center is a vital institution for Mississippi — for health care, for employment, as the center of the capital of the state," he said.

"In my mind, it's a valued resource for this state and community, and we need to do all we can to protect it."

But it wasn't until Rhesa Barksdale set up Donna and Jim on a "blind" date that their earlier, Sweet Potato moment produced a yield. "Six months later, we were married," Donna Barksdale said.

A couple of years later, in 2007, the first Jim and Donna Barksdale Scholars entered the School of Medicine, beneficiaries of grants awarded to all students of merit.

Even more of the state's future physicians found a good reason to be educated at home.

FORTUNE COOKIES:

Dr. Hadley Pearson entered the Ole Miss honors college on a

scholarship named for Sally McDonnell Barksdale. She finished

medical school on the wings of a scholarship named for Jim and

Donna Barksdale.

The Barksdales "have funded my entire education, through college on up," she said. "They've poured a lot of money into me at this point. And so far, all that I've done for them is make them cookies, once.

}They were good cookies, but it doesn't really feel like enough."

Pearson has finished an internship in medicine, preliminary, and is starting a dermatology residency this year at the University of California, San Francisco. After three years, unless a fellowship follows, she'll return to her home state.

Actually, she was born in Puerto Rico — her father had an opportunity to work there — but the family returned to Mississippi when she was 2, to Olive Branch, where she grew up as the daughter of an air traffic controller and a mom who teaches English-language learners.

Pearson, like Shipley, is the first physician in her family. She had fallen in love with medicine after first falling in love with philosophy: Aristotelean ethics — the idea that to best help others, you must develop your talents to the fullest.

"I wanted to make the world a better place than it was in when I found it," Pearson said. "I thought the best way to do that was to become a physician."

Coming up with hundreds of thousands of dollars to get there, though, wouldn't be possible without large student loans, she thought.

"My parents would not have been able to help me pay for medical school," she said. "My grandparents had saved some money for me for college, but certainly not enough for medical school. It would have meant a lot of debt."

The Barksdales changed that. Because of their award to Pearson, Mississippi will have another much-needed specialist in dermatology.

The money her grandparents had saved for her detoured toward the education of her younger siblings: two Mississippi boys and two adopted children from Ethiopia.

"It's amazing how much one or two people can do for a state," she said.

She could have gone to medical school in another state, maybe for less money, or on the strength of large scholarships. But, by the time she had decided to become a physician, "my affection for Mississippi had grown immensely," she said.

So she made an early-decision application to this School of Medicine, and was accepted — before she had been offered the scholarship. "It was a complete surprise to get that in the mail," she said.

Cookies aside, one way to repay the Barksdales, she said, is to "keep the faith in Mississippi." That's how she put it two years ago when she was still a student.

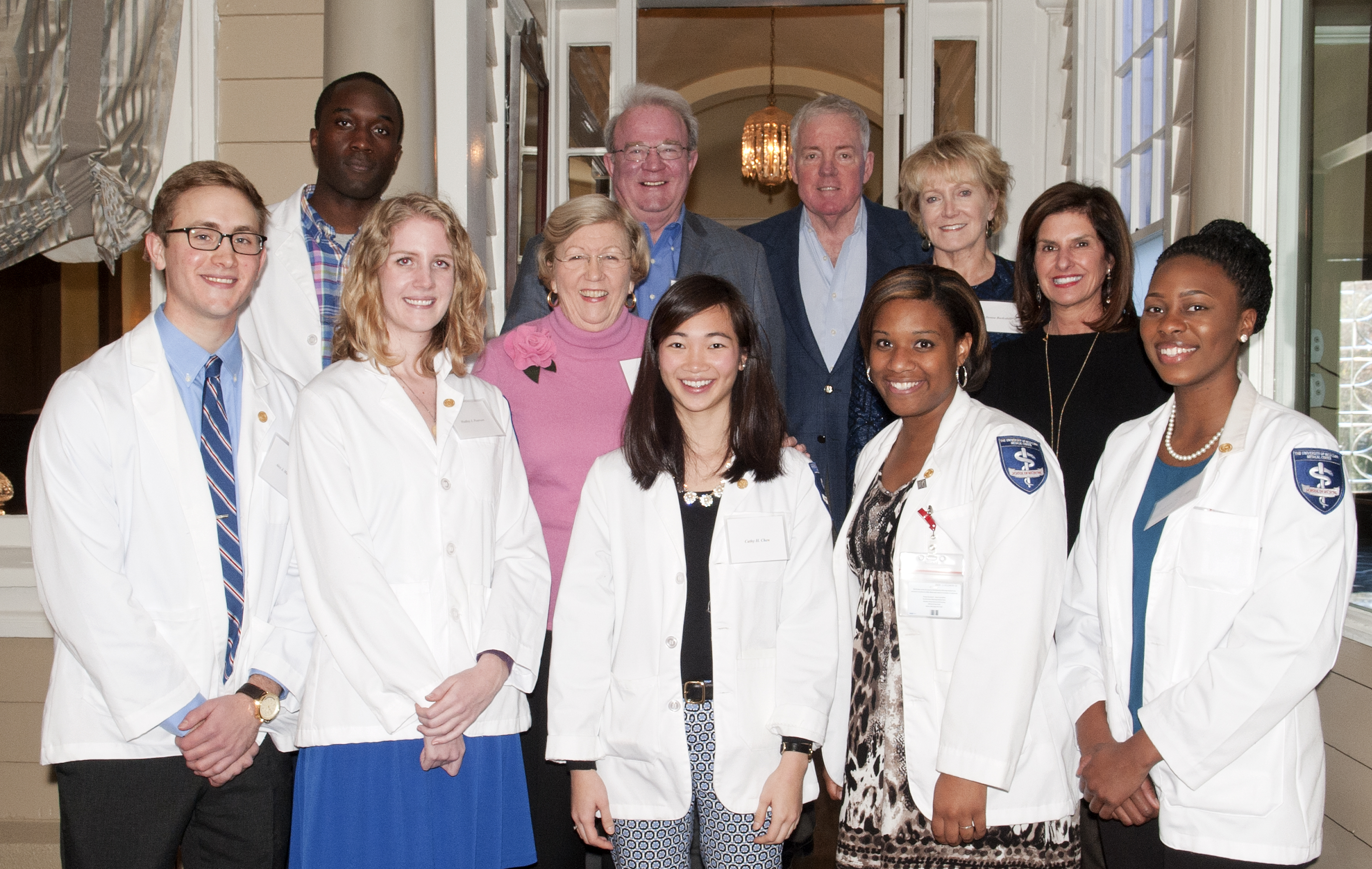

Speaking at the annual Barksdale Scholars luncheon in 2017, she continued: "... I admire the Barksdales, not only for their seemingly limitless generosity to me, but also for their remarkable faith in this state. Loving Mississippi is hard... . They've shown me how much there is to love here, how the people here are good, kind, and smart ... .

"They think this state is worth fighting for, and I hope I can make them proud by doing just that."

ANOTHER DAY, ANOTHER SCHOLAR:

The total number of Barksdale scholars is approaching 90; Dr.

LouAnn Woodward is one of many who is grateful for that number.

"Jim Barksdale and his family have been faithful and steadfast supporters of the Medical Center over many years by actions that are publicly visible and by actions that are much less public, but just as impactful," said Woodward, vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the School of Medicine.

"Jim has been a gracious mentor and advisor to me personally, generously giving of his time and wisdom (and humor)." For the School of Medicine, she said, the family's gifts have been "transformative."

As of early 2019, the Barksdales' medical school contributions topped $17 million, paying for the education of 86 scholars, most of them African-American, and all of them committed to living and practicing medicine in Mississippi for at least five years.

At that same point, 20 of them were in medical school, 20-plus were residents or fellows, and well over 40 had become practicing physicians.

"All those young doctors practicing in Mississippi — I'm delighted," Jim Barksdale said. "So I'd say it's working great."

Where some people see snakes, others see opportunities— to paraphrase Barksdale in "Valley of the Boom."

For the record, Donna Barksdale says Bradley Whitford did a great job.

To support the University of Mississippi Medical Center, visit http://www.umc.edu/givenow/ or contact Jane Harkins, planned giving officer, at 601-984-4468 or [email protected].